Cambridge Zen Center welcomes you to the practice of Zen Buddhism, an ancient tradition that can help you discover your inherent resources of wisdom, love, and compassion. We offer morning and evening Zen practice almost every day of the year, at no charge. BLACK ZEN is a movement dedicated to improving the health and well-being of black and brown communities. It is a social enterprise designed to make meditation accessible, relatable and effective across a dynamic range of individuals.

The goal of this review is to provide a synopsis that practicing clinicians can use as a clinical reference concerning Zen meditation, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). All three approaches originated from Buddhist spiritual practices, but only Zen is an actual Buddhist tradition. You need to enable JavaScript to run this app.

By Leo BabautaThe most important habit I've formed in the last 10 years of forming habits is meditation. Hands down, bar none.

Meditation has helped me to form all my other habits, it's helped me to become more peaceful, more focused, less worried about discomfort, more appreciative and attentive to everything in my life. I'm far from perfect, but it has helped me come a long way.

Probably most importantly, it has helped me understand my own mind. Before I started meditating, I never thought about what was going on inside my head — it would just happen, and I would follow its commands like an automaton. These days, all of that still happens, but more and more, I am aware of what's going on. I can make a choice about whether to follow the commands. I understand myself better (not completely, but better), and that has given me increased flexibility and freedom.

So … I highly recommend this habit. And while I'm not saying it's easy, you can start small and get better and better as you practice. Don't expect to be good at first — that's why it's called 'practice'!

These tips aren't aimed at helping you to become an expert … they should help you get started and keep going. You don't have to implement them all at once — try a few, come back to this article, try one or two more.

- Sit for just two minutes. This will seem ridiculously easy, to just meditate for two minutes. That's perfect. Start with just two minutes a day for a week. If that goes well, increase by another two minutes and do that for a week. If all goes well, by increasing just a little at a time, you'll be meditating for 10 minutes a day in the 2nd month, which is amazing! But start small first.

- Do it first thing each morning. It's easy to say, 'I'll meditate every day,' but then forget to do it. Instead, set a reminder for every morning when you get up, and put a note that says 'meditate' somewhere where you'll see it.

- Don't get caught up in the how — just do. Most people worry about where to sit, how to sit, what cushion to use … this is all nice, but it's not that important to get started. Start just by sitting on a chair, or on your couch. Or on your bed. If you're comfortable on the ground, sit cross-legged. It's just for two minutes at first anyway, so just sit. Later you can worry about optimizing it so you'll be comfortable for longer, but in the beginning it doesn't matter much, just sit somewhere quiet and comfortable.

- Check in with how you're feeling. As you first settle into your meditation session, simply check to see how you're feeling. How does your body feel? What is the quality of your mind? Busy? Tired? Anxious? See whatever you're bringing to this meditation session as completely OK.

- Count your breaths. Now that you're settled in, turn your attention to your breath. Just place the attention on your breath as it comes in, and follow it through your nose all the way down to your lungs. Try counting 'one' as you take in the first breath, then 'two' as you breathe out. Repeat this to the count of 10, then start again at one.

- Come back when you wander. Your mind will wander. This is an almost absolute certainty. There's no problem with that. When you notice your mind wandering, smile, and simply gently return to your breath. Count 'one' again, and start over. You might feel a little frustration, but it's perfectly OK to not stay focused, we all do it. This is the practice, and you won't be good at it for a little while.

- Develop a loving attitude. When you notice thoughts and feelings arising during meditation, as they will, look at them with a friendly attitude. See them as friends, not intruders or enemies. They are a part of you, though not all of you. Be friendly and not harsh.

- Don't worry too much that you're doing it wrong. You will worry you're doing it wrong. That's OK, we all do. You're not doing it wrong. There's no perfect way to do it, just be happy you're doing it.

- Don't worry about clearing the mind. Lots of people think meditation is about clearing your mind, or stopping all thoughts. It's not. This can sometimes happen, but it's not the 'goal' of meditation. If you have thoughts, that's normal. We all do. Our brains are thought factories, and we can't just shut them down. Instead, just try to practice focusing your attention, and practice some more when your mind wanders.

- Stay with whatever arises. When thoughts or feelings arise, and they will, you might try staying with them awhile. Yes, I know I said to return to the breath, but after you practice that for a week, you might also try staying with a thought or feeling that arises. We tend to want to avoid feelings like frustration, anger, anxiety … but an amazingly useful meditation practice is to stay with the feeling for awhile. Just stay, and be curious.

- Get to know yourself. This practice isn't just about focusing your attention, it's about learning how your mind works. What's going on inside there? It's murky, but by watching your mind wander, get frustrated, avoid difficult feelings … you can start to understand yourself.

- Become friends with yourself. As you get to know yourself, do it with a friendly attitude instead of one of criticism. You're getting to know a friend. Smile and give yourself love.

- Do a body scan. Another thing you can do, once you become a little better at following your breath, is focus your attention on one body part at a time. Start at the soles of your feet — how do those feel? Slowly move to your toes, the tops of your feet, your ankles, all the way to the top of your head.

- Notice the light, sounds, energy. Another place to put your attention, again, after you've practice with your breath for at least a week, is the light all around you. Just keep your eyes on one spot, and notice the light in the room you're in. Another day, just focus on noticing sounds. Another day, try to notice the energy in the room all around you (including light and sounds).

- Really commit yourself. Don't just say, 'Sure, I'll try this for a couple days.' Really commit yourself to this. In your mind, be locked in, for at least a month.

- You can do it anywhere. If you're traveling or something comes up in the morning, you can do meditation in your office. In the park. During your commute. As you walk somewhere. Sitting meditation is the best place to start, but in truth, you're practicing for this kind of mindfulness in your entire life.

- Follow guided meditation. If it helps, you can try following guided meditations to start with. My wife is using Tara Brach's guided meditations, and she finds them very helpful.

- Check in with friends. While I like meditating alone, you can do it with your spouse or child or a friend. Or just make a commitment with a friend to check in every morning after meditation. It might help you stick with it for longer.

- Find a community. Even better, find a community of people who are meditating and join them. This might be a Zen or Tibetan community near you (for example), where you go and meditate with them. Or find an online group and check in with them and ask questions, get support, encourage others. My Sea Change Program has a community like that.

- Smile when you're done. When you're finished with your two minutes, smile. Be grateful that you had this time to yourself, that you stuck with your commitment, that you showed yourself that you're trustworthy, where you took the time to get to know yourself and make friends with yourself. That's an amazing two minutes of your life.

Meditation isn't always easy or even peaceful. But it has truly amazing benefits, and you can start today, and continue for the rest of your life.

If you'd like help with mindfulness, check out my new Zen Habits Beginner's Guide to Mindfulness short ebook.

Article

- Historical development

Our editors will review what you've submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

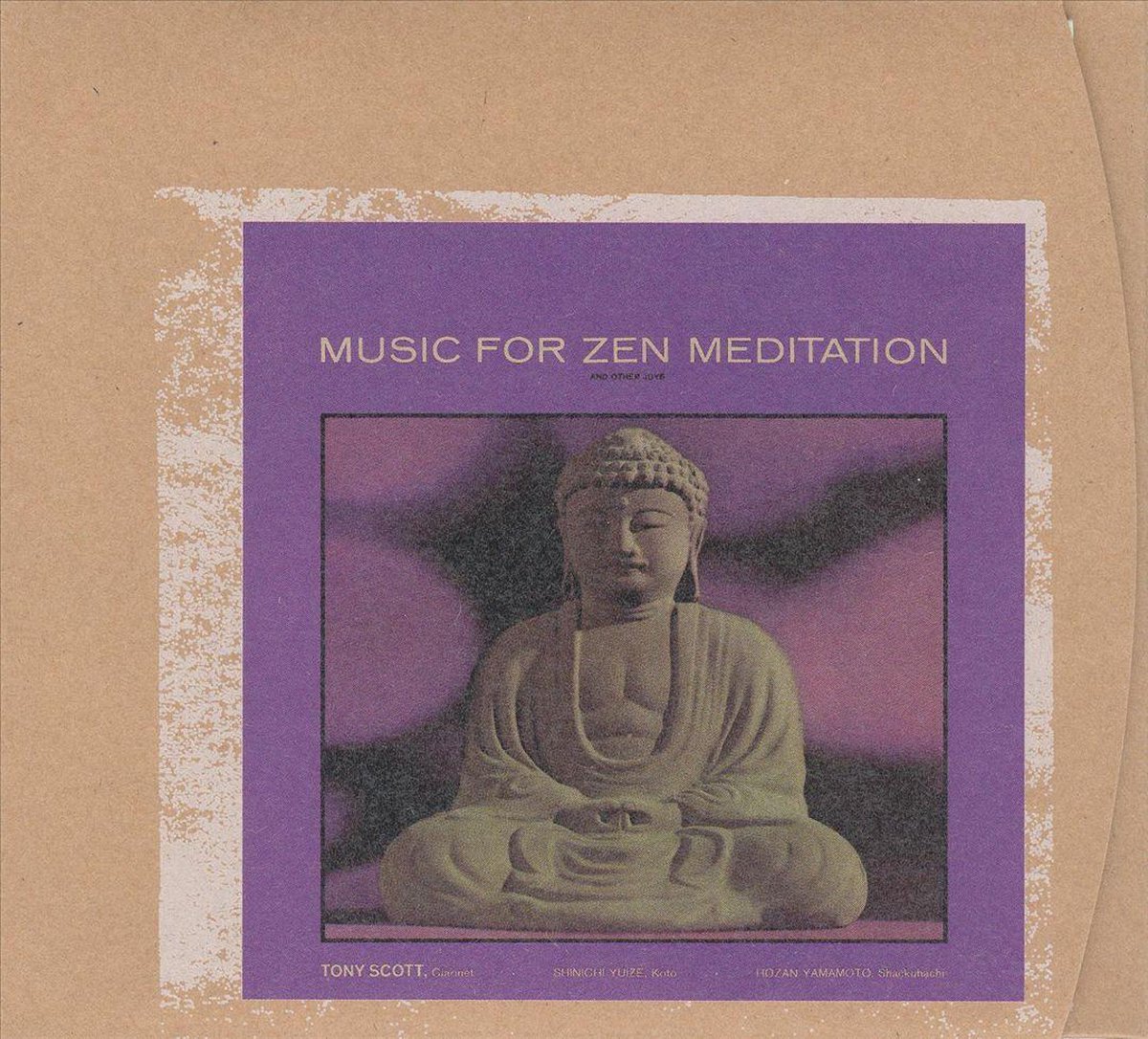

Zen Meditation Images

- Historical development

Our editors will review what you've submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Zen Meditation Images

Join Britannica's Publishing Partner Program and our community of experts to gain a global audience for your work!Zen Meditation Wow

Zen, Chinese Chan, Korean Sŏn, also spelled Seon, Vietnamese Thien, important school of East Asian Buddhism that constitutes the mainstream monastic form of Mahayana Buddhism in China, Korea, and Vietnam and accounts for approximately 20 percent of the Buddhist temples in Japan. The word derives from the Sanskritdhyana, meaning 'meditation.' Central to Zen teaching is the belief that awakening can be achieved by anyone but requires instruction in the proper forms of spiritual cultivation by a master. In modern times, Zen has been identified especially with the secular arts of medieval Japan (such as the tea ceremony, ink painting, and gardening) and with any spontaneous expression of artistic or spiritual vitality regardless of context. In popular usage, the modern non-Buddhist connotations of the word Zen have become so prominent that in many cases the term is used as a label for phenomena that lack any relationship to Zen or are even antithetical to its teachings and practices.

Origins and nature

Compiled by the Chinese Buddhist monk Daoyun in 1004, Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Chingde chongdeng lu) offers an authoritative introduction to the origins and nature of Zen Buddhism. The work describes the Zen school as consisting of the authentic Buddhism practiced by monks and nuns who belong to a large religious family with five main branches, each branch of which demonstrates its legitimacy by performing Confucian-style ancestor rites for its spiritual ancestors or patriarchs. The genealogical tree of this spiritual lineage begins with the seven buddhas, consisting of six mythological Buddhas of previous eons as well as Siddhartha Gautama, or Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha of the current age. The spiritual awakening and wisdom realized by these buddhas then was transmitted from master to disciple across 28 generations of semi-historical or mythological Buddhist teachers in India, concluding with Bodhidharma, the monk who supposedly introduced true Buddhism to China in the 5th century. This true Buddhism held that its practitioners could achieve a sudden awakening to spiritual truth, which they could not accomplish by a mere reading of Buddhist scriptures. As Bodhidharma asserted in a verse attributed to him,

A special transmission outside the scriptures, not relying on words or letters; pointing directly to the human mind, seeing true nature is becoming a Buddha.

From the time of Bodhidharma to the present, each generation of the Zen lineage claimed to have attained the same spiritual awakening as its predecessors, thereby preserving the Buddha's 'lamp of wisdom.' This genealogical ethos confers religious authority on present-day Zen teachers as the legitimate heirs and living representatives of all previous Buddhas and patriarchs. It also provides the context of belief for various Zen rituals, such as funeral services performed by Zen priests and ancestral memorial rites for the families of laypeople who patronize the temples.

The Zen ethos that people in each new generation can and must attain spiritual awakening does not imply any rejection of the usual forms of Buddhist spiritual cultivation, such as the study of scriptures, the performance of good deeds, and the practice of rites and ceremonies, image worship, and ritualized forms of meditation. Zen teachers typically assert rather that all of these practices must be performed correctly as authentic expressions of awakening, as exemplified by previous generations of Zen teachers. For this reason, the Records of the Transmission of the Lamp attributes the development of the standard format and liturgy of the Chinese Buddhist monastic institution to early Zen patriarchs, even though there is no historical evidence to support this claim. Beginning at the time of the Song dynasty (960–1279), Chinese monks composed strict regulations to govern behaviour at all publicly recognized Buddhist monasteries. Known as 'rules of purity' (Chinese: qinggui; Japanese: shingi), these rules were frequently seen as unique expressions of Chinese Zen. In fact, however, the monks largely codified traditional Buddhist priestly norms of behaviour, and, at least in China, the rules were applied to residents of all authorized monasteries, whether affiliated with the Zen school or not.

Zen monks and nuns typically study Buddhist scriptures, Chinese classics, poetics, and Zen literature. Special emphasis traditionally has been placed on the study of 'public cases' (Chinese: gongan; Japanese: kōan), or accounts of episodes in which Zen patriarchs reportedly attained awakening or expressed their awakening in novel and iconoclastic ways, using enigmatic language or gestures. Included in the Records of the Transmission of the Lamp and in other hagiographic compendia, the public cases are likened to legal precedents that are designed to guide the followers of Zen.

Historical development

China

Although Zen Buddhism in China is traditionally dated to the 5th century, it actually first came to prominence in the early 8th century, when Wuhou (625–705), who seized power from the ruling Tangdynasty (618–907) to become empress of the short-lived Zhou dynasty (690–705), patronized Zen teachers as her court priests. After Empress Wuhou died and the Tang dynasty was restored to power, rival sects of Zen appeared whose members claimed to be more legitimate and more orthodox than the Zen teachers who had been associated with the discredited empress. These sectarian rivalries continued until the Song dynasty, when a more inclusive form of Zen became associated with almost all of the official state-sponsored Buddhist monasteries. As the official form of Chinese Buddhism, the Song dynasty version of Zen subsequently spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

During the reign of the Song, Zen mythology, Zen literature, and Zen forms of Buddhist spiritual cultivation underwent important growth. Since that time, Zen teachings have skillfully combined the seemingly opposing elements of mythology and history, iconoclasm and pious worship, freedom and strict monastic discipline, and sudden awakening (Sanskrit: bodhi; Chinese: wu; Japanese: satori) and long master-disciple apprenticeships.

During the Song dynasty the study of public cases became very sophisticated, as Zen monks arranged them into various categories, wrote verse commentaries on them, and advocated new techniques for meditating on their key words. Commentaries such as The Blue Cliff Record (c. 1125; Chinese: Biyan lu; Japanese Heikigan roku) and The Gateless Barrier (1229; Chinese: Wumen guan; Japanese: Mumon kan) remain basic textbooks for Zen students to the present day. The public-case literature validates the sense of liberation and freedom felt by those experiencing spiritual awakening while, at the same time, placing the expression of those impulses under the supervision of well-disciplined senior monks. For this reason, Zen texts frequently assert that genuine awakening cannot be acquired through individual study alone but must be realized through the guidance of an authentic Zen teacher.

Japan

During Japan's medieval period (roughly the 12th through 15th centuries), Zen monks played a major role in introducing the arts and literature of Song-dynasty China to Japanese leaders. The Five Mountain (Japanese: Gozan) Zen temples, which were sponsored by the Japanese imperial family and military rulers, housed many monks who had visited China and had mastered the latest trends of Chinese learning. Monks from these temples were selected to lead trade missions to China, to administer governmental estates, and to teach neo-Confucianism, a form of Confucianism developed under the Song dynasty that combined cultivation of the self with concerns for social ethics and metaphysics. In this way, wealthy Zen monasteries, especially those located in the Japanese capital city of Kyōto, became centres for the importation and dissemination of Chinese techniques of printing, painting, calligraphy, poetics, ceramics, and garden design—the so-called Zen arts, or (in China) Song-dynasty arts.

Apart from the elite Five Mountain institutions, Japanese Zen monks and nuns founded many monasteries and temples in the rural countryside. Unlike their urban counterparts, monks and nuns in rural Zen monasteries devoted more energy to religious matters than to Chinese arts and learning. Their daily lives focused on worship ceremonies, ritual periods of 'sitting Zen' (Japanese: zazen) meditation, the study of public cases, and the performance of religious services for lower-status merchants, warriors, and peasants. Rural Zen monks helped to popularize many Buddhist rituals now common in Japan, such as prayer rites for worldly benefits, conferment of precept lineages on lay people, funerals, ancestral memorials, and exorcisms. After the political upheavals of the 15th and 16th centuries, when much of the city of Kyōto was destroyed in a widespread civil war, monks from rural Zen lineages came to dominate all Zen institutions in Japan, including the urban ones that formerly enjoyed Five Mountain status.

After the Tokugawa rulers of the Edo period (1603–1867) restored peace, Zen monasteries and all other religious institutions in Japan cooperated in the government's efforts to regulate society. In this new political environment, Zen monks and other religious leaders taught a form of conventional morality (Japanese: tsūzoku dōtoku) that owed more to Confucian than to Buddhist traditions; indeed, Buddhist teachings were used to justify the strict social hierarchy enforced by the government. Many Confucian teachers in turn adapted Zen Buddhist meditation techniques to 'quiet sitting' (Japanese: seiza), a Confucian contemplative practice. As a result of these developments, the social and religious distinctions between Zen practice and Confucianism became blurred.

When the Ming dynasty (1368–1661) in China began to collapse, many Chinese Zen monks sought refuge in Japan. Their arrival caused Japanese Zen monks to question whether their Japanese teachers or the new Chinese arrivals had more faithfully maintained the traditions of the ancient buddhas and patriarchs. The resultant search for authentic Zen roots prompted the development of sectarianism, not just between Japanese and Chinese Zen leaders but also within the existing Japanese Zen community. Eventually sectarian rivalry led to the emergence of three separate Japanese Zen lineages: Ōbaku (Chinese: Huanbo), Rinzai (Chinese: Linji), and Sōtō (Chinese: Caodong). Ignoring their similarities, each lineage exaggerated its distinctive features. Thus, both Rinzai and Sōtō emphasized their adherence to certain Song-dynasty practices, in contrast to the Ōbaku monasteries, which favoured Ming traditions, especially in such areas as ritual language, musical instruments, clothing, and temple architecture. People affiliated with Sōtō, by far the largest of the Japanese Zen lineages, stressed the accomplishments of their patriarch Dōgen (1200–53), whose chief work, Shōbōgenzō (1231–53; 'Treasury of the True Dharma Eye'), is widely regarded as one of the great classics of Japanese Buddhism.

Zen Meditation App

- related people

- areas of involvement